|

| General Pershing salutes New York |

General Pershing had commanded the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I. He left the United States in June 1917, just months after the U.S. declared war against Germany on April 6, 1917. He would not return for more than two years.

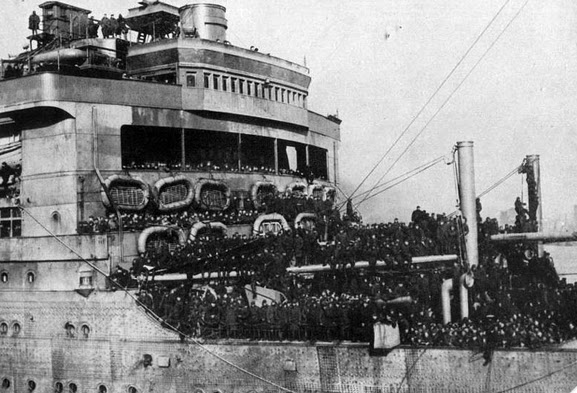

Just months after the signing of the treaties that officially ended the war in June 1919, --and after the numerous celebrations honoring Pershing that were held in France and England --Pershing sailed from Europe on the Leviathan, (a German ship seized by the U.S. in 1917). The troop ship had crossed the Atlantic many times during the war, transporting a large share of the more than 2 million American soldiers who would eventually serve in France.

|

| Homecoming: SS Leviathan |

Millions of "loyal citizens of the great metropolis of the world," Hylan wrote to the general, "eagerly and impatiently await the opportunity to give their plaudits to the man through whose instrumentality the magnificent achievements of our armies were made possible."

The city was beside itself with excitement to welcome the valorous general back on American soil.

When Pershing set foot on New York soil (the Battery), he was observed to have tears streaming down his cheeks at the sight of the welcoming crowds. The crowds themselves were brimming with enthusiasm, and he was soon on his way to City Hall for a reception. Accompanying Pershing was his 10 year old son, Warren, who, just days earlier, had the honor of informing the general that he had been appointed "General of the Armies," the highest rank of any American military officer in history.*

Over the next couple of days, Pershing was feted by the thousands of Americans who came out to welcome him. You can watch the footage of his New York welcome in 1919 here.

|

| Pershing in Central Park: crowds jammed the greensward that day |

|

| Through the Arch of Victory, NYC |

The New York City Board of Alderman approved the construction of the arch on December 3, 1918, just weeks after the Armistice had gone into effect on November 11, 1918. Mayor Hylan approved the resolution which appropriated $80,000 for the construction of the arch.

|

| Is it a little "over the top"? |

During Pershing's big welcome home extravaganza the arch still stood. It was, after all, pretty hard to miss. Crazy with ornate detail, its architectural exuberance well matched to the spirit of New York in full flush of "victory."

|

| Is my hat on straight? |

At City Hall, all the big-wig politicians were present and assembled, including Secretary of War

Newton Baker, New York governor Al Smith, and mayor John Hylan. Everyone wanted to get in on the spectacle.

A surprise awaited the general at City Hall when a young woman burst past the police lines and kissed him on the cheek. The crowd erupted in cheers. Another woman tried to follow suit, but the general stopped her in her tracks. "O, madam," he exclaimed, "please don't."

|

| "Who was that lady, Dad?" Warren Pershing |

Pershing was, after all, with his young son!

Meanwhile: Stories of kissing and being kissed by Pershing seemed to circulate widely--perhaps they symbolically represented the city's feeling of l'amour for him--one story told of a woman, Kitty Dalton, who was the kissee. "Can he kiss?" she was asked after he reportedly "kissed her a regular American man's smacker" when she presented him with roses. "I'd say he can," Kitty dished. "He kissed me full on the lips.. . nobody ever kissed me as Gen. Pershing did."("Can He Kiss? This Girl Says Pershing Can," New York Times, September 11, 1919.

After the City Hall reception, Pershing's motorcade traveled to the Waldorf Hotel (Pershing and Warren stayed in the hotel's "pink and gold suite," reporter Percy Hammond noted) via Lafayette Street to Ninth, then to 5th Avenue and to the hotel's entrance on 33rd Street. That evening, he, Warren, and a group of VIPs dined at the Ritz-Carlton and then were entertained (along with 5,000 others) at the Hippodrome Theater at 6th Ave and 44th Street.

Pershing's first full day back in the United States, September 10, 1919, was jam packed.

At the Sheep Meadow in Central Park, he would greet a crowd of 50,000 people, 30,000 of which were school children. Some waited three hours just to catch a glimpse of the general.

|

| Jubilance, American Style |

The general also conducted an "inspection" of cadets outside of Wanamaker's Department Store at 770 Broadway at 9th Street (the site of the defunct A.T. Stewart store).

|

| A full day's honor |

At 10:30 AM the next day, a parade was planned with Pershing leading it, traveling from 110th Street to Washington Square. It would take the parade a total of three hours to complete.

Pershing was particularly looking forward to riding his horse, Kidron (1907-1942), in the parade. Kidron had been given to him in France and the general had ridden him in various ceremonies and parades in Paris, including the victory parade through l'arc de triomphe. But Kidron had been in quarantine in Newport News, VA, since arriving from France and the U.S. Department of Agriculture refused to release the sorrel horse in time for the parade.

And so Pershing had to ride another horse.

|

| Pershing and Kidron, who became, Pershing reported, "a naturalized and enthusiastic loyal American." |

|

| "And We Did Come Back! It's Over Over There," Parade of US Soldiers, Fifth Avenue |

Pershing was proud to lead the parade of soldiers of the First Division. Among this unit were the first American troops in France, the men who had marched with Pershing in Paris upon their arrival "over there." "Layfayette," they announced at the tomb of the French general who had fought alongside George Washington, "Nous sommes ici." (We are here!)

Also marching with Pershing was the "Composite Regiment," a group of U.S. soldiers of various ranks and from various units that represented the "best" of the armed forces.

|

| Composite Regiment with Pershing, SS Leviathan, September 1919 |

|

| Sergeant Johnson's Homecoming |

This was perhaps no surprise owing to the complete segregation of the U.S. Armed Forces at the time. But still, it is hard to imagine that so many brave Americans (never mind New Yorkers!) were left out of the "representative" unit.

The city had celebrated its own, however. In February 1919, New York had welcomed the famed members of the 369th Infantry Regiment (the Harlem Hellfighters), who had all been awarded the Croix de Guerre, France's highest award for bravery. Nearly 250,000 New Yorkers turned out to welcome them, as they marched and rode in a parade along 5th Avenue.

Among them was Sergeant Henry Johnson (1891-1929) who enlisted in June 1917 in Brooklyn. His heroism would not be "officially" recognized by the U.S. military until nearly a century after the war: See Henry Johnson's story here.)

|

| On Fifth Avenue, a Three-Hour Parade |

Pershing's victory parade was a much larger affair, to be sure. And despite the numerous parade participants, it was really only one single man that the crowds wanted to see.

"General Pershing was a handsome martial figure as his horse two-stepped past the Metropolitan museum," reported Percy Hammond, "saluted the secretary of war with ample and a gracious dignity. . . it was his crowded hour." ("Pershing Leads First Division in Glory March," New York Times, September 11, 1919.)

A carillon of bells played "The Star Spangled Banner" as the parade made its way down Fifth Avenue.

After he had ridden the parade route, Pershing returned to his hotel, where, from his suite's balcony, he would observe troops passing in review.

In the evening it was back to Central Park for a concert, and then it was on to dinner at the Waldorf.

Just a small dinner of 1,600 guests.

|

| Is that a feather in your cap, General? |

And indeed, Pershing had steered a course through the first truly modern industrialized war. He had been up against the mammoth egos of French and British generals who scoffed at the upstart American (while overseeing the slaughter--in the millions-- of their own armies.) Pershing had fought successfully to maintain the American army and not let the Allies simply use as cannon fodder the Americans in their own bloodied ranks. And he had more than proven his skill as a strategist and military leader.

And he had also endured unspeakable personal tragedy.

He more than deserved the fanfare and kisses, the "paper showers" and cheers.

|

| A La Jeune Fille de France by Micheline Resco |

And if only--could he dare to think it?--if only he could be reunited with someone who remained in Paris, the love of his life, Micheline Resco, then victory would truly be his.

Ah, Micheline! Pershing no doubt wished that the young woman he met in Paris upon his arrival in the summer of 1917 could be by his side. Micheline, an artist, would soon paint a portrait of Pershing, an image of the victorious general as the world, and as New York chose to see him.

But despite the very public display of affection he received by the city, Pershing still wanted something more. The millions of New Yorkers would never know that something was missing upon his return to the United States.

He would have to wait for another homecoming of sorts. This one would take place when another ship sailed into New York Harbor. It arrived from Le Havre, France, on August 30, 1920. On board was Micheline, finally reunited with Pershing.

No newspapers would report on this arrival. No reporters would know. Pershing and Micheline would continue the romantic relationship that they had begun that summer in 1917 and would last--in secrecy-- for the entirety of Pershing's life.

To her kisses, Pershing might have responded, "O, mademoiselle, please do."

~Jenny Thompson

|

| A New York Arrival, Just for Two, August 1920 |

No comments:

Post a Comment