|

| George: "Mary, Please come with me to New York!" (Illustration by Norman Rockwell, 1932) |

On

April 23, 1789, just one week before being sworn in as the first

president of the United States, George Washington and his staff settled

into the country's first executive mansion, located at 10 Cherry Street in New York City. For nearly two years, before being moved to Philadelphia, the

seat of the U.S. government would be located in New York City; and

Manhattan would be home to the President and First Lady. The new nation was just starting to recover

from the long years of war, and nowhere was this better in evidence than

in Manhattan.

|

|

| A New New York |

|

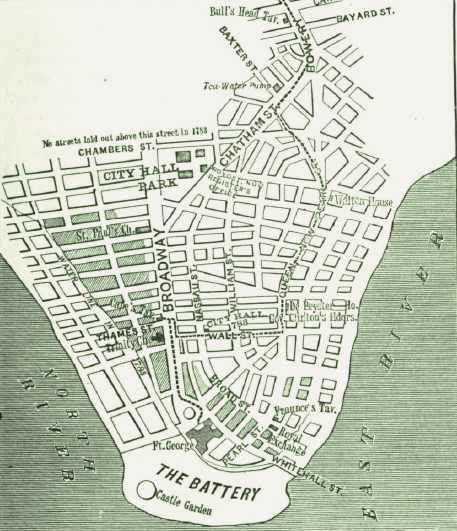

| NYC 1783: Concentrated Population |

"Every

dwelling-house was occupied. Rents went up, doubling in some instances;

fresh paint and new shutters and wings transformed old tenements, and

carpenters and masons found ready employment in erecting new structures.

The streets were cleaned and pavements mended. New business firms were

organized and old warehouses remodeled; the markets were extended and

bountifully supplied, and stores blossomed with fashionable goods. Wall

Street, the great centre of interest and of fashion, presented a

brilliant scene every bright afternoon."

|

| On Broadway, 1780s |

|

| Fashionable Promenading |

"Ladies in showy costumes, and gentlemen in silks, satins, and velvet, of many colors, promenaded in front of the City Hall — where Congress was holding its sessions. At the same time Broadway, from St. Paul's Chapel to the Battery, was animated with stylish equipages, filled with pleasure seekers who never tired of the life-giving, invigorating, perennial seabreeze, or the unparalleled beauty of the view, stretching off across the varied waters of New York Bay."

In a "new" New York, on April 30, 1789, George Washington took the oath of office at Federal Hall in New York City (demolished 1812).

There was little fanfare, and Washington's inaugural address was brief, befitting the Federalism of a new nation. The frills and follies of the British Empire were gone, and "simplicity" now reigned.

|

| A New Nation: Simple, Proud, and Orderly |

In the spring of 1789, Martha Washington was preparing to join her husband in New York. And she planned to be present for his inauguration.

But she lingered at Mount Vernon, in Virginia, at the home she loved dearly.

|

| A Quiet Place, Martha's Home, Mount Vernon |

And during the Revolution, it was New York City that had been an epicenter of the war, occupied by the British from 1776 to 1783.

|

| Pulling Down the King: Bowling Green, NYC, 1776 |

All of that had been just a few years prior to the Washington's move to Manhattan. But now the city was in a state of renewal.

|

| "Good-bye Red Coats. Hello New York!" |

She missed the swearing-in ceremony. Her husband was already president by the time she arrived.

|

| "The Lady of his Excellency" Arrives |

Then, "the entire party was conducted over the bay in 'the President's Barge, rowed by 13 eminent pilots, in a handsome white dress.' On passing the Battery a salute of thirteen heavy guns was fired, and on landing at Peck's Slip Mrs. Washington was welcomed by crowds of citizens who had assembled to testify their joy upon this happy occasion, while prolonged cheers, and shouts of 'Long live President Washington and God bless Lady Washington' were heard on all sides." Anne Hollingsworth Wharton, Martha Washington. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1897, 192.

|

| Cherry Street, NYC |

The

President's "apartments" in Cherry Street

was a house built by Revolutionary War veteran Samuel Osgood in 1770.

(Osgood was later Postmaster General. His NYC house was demolished in

1856. But his Massachusetts house still exists. )

In preparation for the first American President's

occupancy (the residence would also serve as the executive office), the

house had been renovated and furnished with newly built mahogany furniture;

and the walls had been newly papered.

"The mansion was quite elegant and spacious for the time," wrote historian Benson John Lossing in Mary and Martha, the Mother and the Wife of George Washington. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1886. It was "in a very respectable, though not in the most fashionable, quarter of the city, which was then in Wall and Broad streets. It was regarded as 'up-town.' The situation was pleasant, for in front of it flowed the broad East River, beyond which were the little village of Brooklyn and the green forests of Long Island."

"The mansion was quite elegant and spacious for the time," wrote historian Benson John Lossing in Mary and Martha, the Mother and the Wife of George Washington. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1886. It was "in a very respectable, though not in the most fashionable, quarter of the city, which was then in Wall and Broad streets. It was regarded as 'up-town.' The situation was pleasant, for in front of it flowed the broad East River, beyond which were the little village of Brooklyn and the green forests of Long Island."

|

| Mrs. Washington: Not So Very Publick |

"I little thought when the war was finished," Martha wrote to a friend, "that any Circumstances could possibly happen which would call the General into public life again. I had anticipated that, from that moment, we should be suffered to grow old together in solitude and tranquility."

In another letter to a friend, (dated October 22, 1789), she wrote:

Mrs. Washington did meet her obligations, however, and hosted "state dinners" with the General every week. Despite her claim of being home bound, she enjoyed going to the theater, and held formal dinners on Thursdays and public receptions on Fridays.

"More than one description has come down to us of Lady Washington’s Friday evening receptions," wrote historian Anne Hollingsworth Wharton, "with their plum-cake, tea, coffee, and pleasant intercourse, — all ending at the early hour of nine. There was nothing excessive in the gayety of these drawing-rooms, and they may even have been a trifle dull; but the hostess wisely set the fashion of early hours, rising about nine o'clock, and saying, with a graciousness and dignity that well became her, 'The General always retires at nine, and I usually precede him.' The short evening proved to be like the small caviare sandwiches that are now handed around to whet the appetite, making the guests feel like coming again; for these receptions were largely attended by the old Knickerbocker and Patroon families,—the Wons and the Wans, – as well as by the wives and daughters of all government officials resident at the capital," Anne Hollingsworth Wharton, Martha Washington, 197.

_-_Daniel_Huntington_-_overall.jpg) |

| "It's almost 9 o'clock, everyone!" A Presidential Reception in NYC |

The Wons and the Wans may not have

wanted to leave the Washingtons' house so early. Still, they turned out

when invited. For, it was the "social ticket" to receive.

Sometimes, there was even a little bit of drama:

"Mrs. Washington's drawing-rooms, on Friday nights, were attended by the grace and beauty of New York. On one of these occasions an incident occurred which might have been attended by serious consequences. Owing to the lowness of the ceiling in the drawing-room, the ostrich feathers in the head-dress, of Miss Mclver, a belle of New York, took fire from the chandelier, to the no small alarm of the company. Major Jackson, aid-de-camp to the President, with great presence of mind, and equal gallantry, flew to the rescue of the lady, and, by clapping the burning plumes between his hands, extinguished the flame, and the drawing-room went on as usual." George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington. Washington, DC: William H. Moore, 1859: 59.

Despite the occasional drama in the drawing room, the social life of the upper classes in New York was flourishing. "The luxury and ostentatious display of riches in the city," observed French writer and soon-to-be French Revolutionary Brissot de Warville, "were great." The ladies, he remarked, were "especially extravagant in their dress."

True, the New New Yorkers had a taste for the good life.

But they did win over the President with their simple New Year's Day tradition of calling upon their friends. The President first experienced this tradition on New Year's Day, 1790, when the weather in New York City was closer to a day in May than January. Visitors arrived at the Washington home following a long observed custom "derived from Dutch forefathers" of the city.

General Washington delighted in this and remarked: “The highly favored situation of New York will, in the process of years, attract numerous emigrants, who will gradually change its ancient customs and manners; but let whatever changes take place, never forget the cordial, cheerful observances of New Year's day.”

Sometimes, there was even a little bit of drama:

"Mrs. Washington's drawing-rooms, on Friday nights, were attended by the grace and beauty of New York. On one of these occasions an incident occurred which might have been attended by serious consequences. Owing to the lowness of the ceiling in the drawing-room, the ostrich feathers in the head-dress, of Miss Mclver, a belle of New York, took fire from the chandelier, to the no small alarm of the company. Major Jackson, aid-de-camp to the President, with great presence of mind, and equal gallantry, flew to the rescue of the lady, and, by clapping the burning plumes between his hands, extinguished the flame, and the drawing-room went on as usual." George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington. Washington, DC: William H. Moore, 1859: 59.

Despite the occasional drama in the drawing room, the social life of the upper classes in New York was flourishing. "The luxury and ostentatious display of riches in the city," observed French writer and soon-to-be French Revolutionary Brissot de Warville, "were great." The ladies, he remarked, were "especially extravagant in their dress."

True, the New New Yorkers had a taste for the good life.

But they did win over the President with their simple New Year's Day tradition of calling upon their friends. The President first experienced this tradition on New Year's Day, 1790, when the weather in New York City was closer to a day in May than January. Visitors arrived at the Washington home following a long observed custom "derived from Dutch forefathers" of the city.

General Washington delighted in this and remarked: “The highly favored situation of New York will, in the process of years, attract numerous emigrants, who will gradually change its ancient customs and manners; but let whatever changes take place, never forget the cordial, cheerful observances of New Year's day.”

|

| The "Mansion House," the Washingtons' more commodious house at 39-41 Broadway, near Bowling Green |

The

Washingtons spent just ten months in their rented house on Cherry

Street. On February 23, they would move to the much larger Alexander

Macomb House, also known as the "Mansion House," just south of Trinity

Church, at 39-41 Broadway (demolished in 1940). There they remained until August 30, 1790.

"The situation was delightful" at the Mansion House. "The location was better than the Cherry Street house, and there were grassy slopes from the house to the Hudson River, and far away to the westward spread out the fields and forests of New Jersey," Lossing, 289.

Before their move, from December through January 1790, the painter Edward Savage (1789-96) visited the Washingtons in their Cherry Street home to make sketches for a group portrait that would be displayed publicly in 1796. (The painting is now in the collection of the National Galley of Art.)

"The situation was delightful" at the Mansion House. "The location was better than the Cherry Street house, and there were grassy slopes from the house to the Hudson River, and far away to the westward spread out the fields and forests of New Jersey," Lossing, 289.

Before their move, from December through January 1790, the painter Edward Savage (1789-96) visited the Washingtons in their Cherry Street home to make sketches for a group portrait that would be displayed publicly in 1796. (The painting is now in the collection of the National Galley of Art.)

|

| In NYC: George, George, Eleanor, Martha, and "Servant." |

The

Washingtons strike a formal pose for the viewer; they show themselves

residing among the trappings of knowledge and good breeding; General

Washington's sword is in repose; and land--seemingly endless and

idyllic-- spreads out behind them in typical American mythological

fashion. These are people whose "self-interest" is, in the words of Alexis de Tocqueville, "rightly understood."

Pictured with George and Martha are George Washington Parke Custis and Eleanor Parke Custis, Martha's grandchildren, who lived with the Washingtons at Mount Vernon following the death of their father, and who also came with them to live in New York.

The man in the painting identified by the National Galley of Art as a "servant" was actually one of the seven enslaved workers George Washington took with him from Mount Vernon to New York in 1789. (The Washingtons' "ownership" of enslaved people has been well-documented and continues to be studied and critiqued).

The seven enslaved workers who lived with the Washingtons at Cherry Street and later Broadway included: Austin, Giles, Paris, Moll, Christopher Sheels, William Lee, and Oney "Ona" Judge. Moll was nursemaid to little George and Eleanor.

In the portrait, Mrs. Washington is shown pointing on a map to a location for the future site of the U.S. Government: Washington, D.C.

No doubt she wished to escape from New York, and one year later, the Washingtons moved, along with the seat of the American government, to Philadelphia. While Mrs. Washington was not free from her public duties, she was more comfortable in her publick role.

But there were others in the Washington household who longed for their freedom too.

One of them would attain that freedom after the move to Philadelphia; In May 1796, Oney Judge escaped from the household while the Washingtons were eating dinner. She was assisted in her escape and brought to New Hampshire. There she would learn to read, get married, and raise a family.

It was reported to the Washingtons that "a thirst for compleat freedom. . .had been her only motive for absconding." In fact, Martha Washington was preparing to give Oney to a relative as "a wedding present."

Martha and Oney. Two women in a "new" New York.

Both longed for the lives they dreamed for themselves.

They

found themselves in a city that was coming into its own: fashion,

tradition, society, and politics were key components to this new

Federalist town. The Revolution was done.

But New York in the 1790s was also just beginning its trajectory into a modern world. When the Washingtons called it home, American democracy was just beginning to be defined and tested. And the new city was not only full of the swaggering and promenading new Americans, but it was also full of enslaved people- constituting roughly one quarter of the population. During the Revolution, 10,000 enslaved people had, in fact, come to New York City. They came after hearing that the British promised them their freedom if they reached the British lines.

New York was then, and perhaps remains to some extent, a place where people go to escape, to find freedom and the lives they dream for themselves. It is also a place from which people wish to flee. The dream of a better place is truly a constant in American history.

~Jenny Thompson

Pictured with George and Martha are George Washington Parke Custis and Eleanor Parke Custis, Martha's grandchildren, who lived with the Washingtons at Mount Vernon following the death of their father, and who also came with them to live in New York.

The man in the painting identified by the National Galley of Art as a "servant" was actually one of the seven enslaved workers George Washington took with him from Mount Vernon to New York in 1789. (The Washingtons' "ownership" of enslaved people has been well-documented and continues to be studied and critiqued).

The seven enslaved workers who lived with the Washingtons at Cherry Street and later Broadway included: Austin, Giles, Paris, Moll, Christopher Sheels, William Lee, and Oney "Ona" Judge. Moll was nursemaid to little George and Eleanor.

In the portrait, Mrs. Washington is shown pointing on a map to a location for the future site of the U.S. Government: Washington, D.C.

No doubt she wished to escape from New York, and one year later, the Washingtons moved, along with the seat of the American government, to Philadelphia. While Mrs. Washington was not free from her public duties, she was more comfortable in her publick role.

But there were others in the Washington household who longed for their freedom too.

One of them would attain that freedom after the move to Philadelphia; In May 1796, Oney Judge escaped from the household while the Washingtons were eating dinner. She was assisted in her escape and brought to New Hampshire. There she would learn to read, get married, and raise a family.

It was reported to the Washingtons that "a thirst for compleat freedom. . .had been her only motive for absconding." In fact, Martha Washington was preparing to give Oney to a relative as "a wedding present."

| |

|

Both longed for the lives they dreamed for themselves.

|

| Only Compleat Freedom |

But New York in the 1790s was also just beginning its trajectory into a modern world. When the Washingtons called it home, American democracy was just beginning to be defined and tested. And the new city was not only full of the swaggering and promenading new Americans, but it was also full of enslaved people- constituting roughly one quarter of the population. During the Revolution, 10,000 enslaved people had, in fact, come to New York City. They came after hearing that the British promised them their freedom if they reached the British lines.

New York was then, and perhaps remains to some extent, a place where people go to escape, to find freedom and the lives they dream for themselves. It is also a place from which people wish to flee. The dream of a better place is truly a constant in American history.

~Jenny Thompson

No comments:

Post a Comment