|

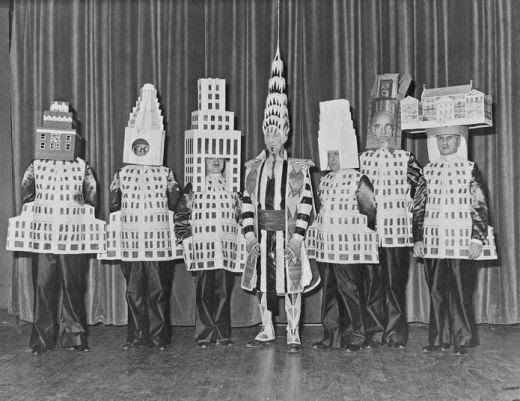

| 1931: A Dazzling New York Skyline of Architects |

Photo: L-R:

A. Stewart Walker (Fuller Building), Leonard Schultze

(Waldorf-Astoria), Ely Jacques Kahn (Squibb Building), William Van Alen

(Chrysler Building), Ralph Walker (1 Wall Street), D.E.Ward

(Metropolitan Tower), Joseph H. Freelander (Museum of New York).

At the Beaux-Arts Ball held in New York City on January 23, 1931, the party was not to be topped...but some of the attendees were!

|

| The Chrysler Building |

Architect William Van Alen's famous Chrysler Building had been completed the year before. So perhaps it was fitting that his costume would stand out above the crowd. His building was a feat of engineering, and its Art Deco style reflected the American spirit of the time: the verve and the daring that produced so many of America's best achievements.

|

| William Van Alen: A Spirit of the Times |

The Beaux Arts ball signaled a shift in design not only in architecture, but also in fashion. Although it was a group of men whose costumes were inspired by their own buildings' designs, women were prominently (and daily) out and about on the streets wearing clothes that also seemed informed by the modern shapes and styles of the Art Deco era.

It was in the 1930s that women's clothing would take a turn away from the Flapper-era boyish short skirts, to favor the sleek, body-hugging long silhouettes that seemed to mirror the city skyline.

|

| Form Follows Fashion, 1930s Designs |

This new form moved away from the boxy and straight shapes of the 1920s. Now the figure itself was suggested, but not revealed, hidden, as it were, beneath a sheath that was sexy and even structural.

|

| Shades of Chrysler?: A Madeleine Vionnet design, 1938 |

"Ungainly women must be jubilant," observed an editor for Vogue, "for the new clothes are extremely becoming, and a multitude of sins can be hidden beneath the new draperies."

Ironically, Van Alen's iconic building would also prove to cloak a multitude of sins; famously, Van Alen had a falling out with William Chrysler, the building's namesake. By the time the building was being oohed and aahed at in NYC and around the world, Van Alen was all but "hidden beneath the new draperies" of the fanfare; his name not even uttered by Chrysler.

|

| You're the Top: The Chrysler Building |

The Chrysler Building only held the title of tallest building for about a year. In 1931, the newly-completed Empire State Building would clinch that title.

For Van Alen, who had been born in Brooklyn and worked for a stunning number of architectural firms in NYC through his career, the city remained his home.

Daily, perhaps, he could glimpse the very thing he'd created.

Ultimately, the Chrysler Building is the perfect symbol of 1930s New York. It was the sign of hope, of engineering, of industry. It put thousands to work during construction. It stood for the power of the American economy.

But it was also a sign of a kind of folly. The Depression would begin in earnest just after it was completed; and there the building stood, a reminder to everyone, not just Van Alen, of earlier, headier times.

Now, in this new post-1929 age, the future was looked at with fingers crossed. Now, workers teetered on the edge, out of work, or making just enough to get by. The city would keep moving though; Van Alen would turn to teaching, and waiters would continue to serve their patrons, whether those patrons were dining with the city at their feet or dressing up like buildings and attending the Beaux Arts Ball.

~Jenny Thompson

|

| At Your Service: New York City in the 1930s |

2 comments:

Awesome Ms. Thompson... I am happy to be able to read your writing again...

Thank you so much, Brian!

Post a Comment