|

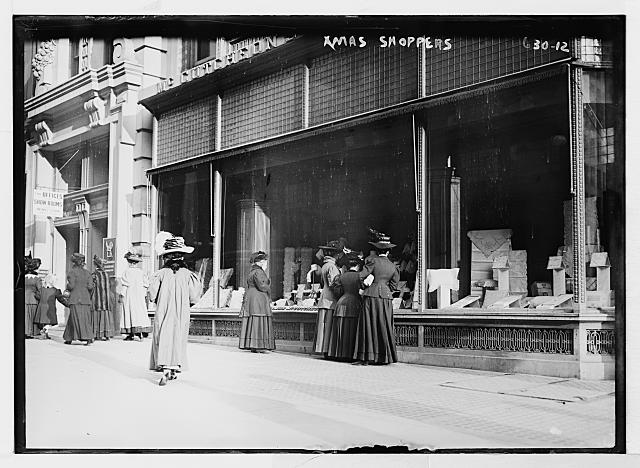

| Christmas Card Display: the observed and the observer |

From any recent study of New York the

visitor from another planet would conclude that our observance of

Christmas consisted chiefly in unusual practice and encouragement of the

art of shop-keeping. Broadway and the other shopping streets

have been for many days a vast fair, crowded with customers till long

past the dinner-hour, and late at night, no doubt, the shopmen went out

and bought from each other, for there is no resisting the contagion.

When one has bought what he desires, there is a fine pleasure in

leisurely strolls through the shopping quarter.

J. E. Learned, "Christmas Streets," New Outlook, December 1892

Ah, Christmas!

Late 19th century and early 20th century images depicting Christmas in New York from the Library of Congress collection can be divided (roughly) into two types: those showing activities related tocharities (Salvation Army, soup kitchens, orphanages, et al) and those showing shoppers on the street.

|

| Children looking into Macy's Department Store window, New York City, c. 1914 |

In relation to the latter subject, the camera's point of view is that of the observer--observing those who are themselves observing. The camera's subject is the people on the street who have paused to look at window displays and are strolling along the street "window shopping."

|

| Window Shoppers, NYC |

There's a little shop half a flight up, on Fortieth Street, in New York, whose

windows are always especially attractive—one of those upstairs apparel

shops with all manner of dainty things. A neatly lettered card in the window suggests in a businesslike yet friendly manner that the "window shopper"

come in and look around.

"We thank you for stopping — for stopping to look at our display of merchandise We hope that it pleased you, and if you are anxious for further information, come inside. If you are not ready to buy, thanks anyway for stopping," reads the card.

"We thank you for stopping — for stopping to look at our display of merchandise We hope that it pleased you, and if you are anxious for further information, come inside. If you are not ready to buy, thanks anyway for stopping," reads the card.

"Thank You Card," The Spatula, June 1921.

It took time before many merchants recognized the valuable advertisement that a store could broadcast through a window pane, but once they did, window displays became ever more prominent and elaborate.

Soon, they would even be lit at night.

|

| Printer's Ink, April 10, 1907 |

In 1908, a New York merchant commented on the value of the night shop window, noting:

“I have frequently seen men and women too, who were window shopping before my place at night inside the next day. People in New York keep posted on the fashions and on what is to be had in the stores by 'window shopping.’ ” (Trade: A Journal for Retail Merchants, 1908).

Women in particular were targeted by shop keepers through the window display. Women, it was argued, "can either 'window shop' or 'window wish' without embarrassment. There are no clerks to ask her this or that until

her mind is made up. Women are guided and influenced by window displays, I believe, in fully 80 per cent of their purchases," A.G. Sten, "Why Show Windows Appeal," The Dry Goods Reporter, 1912.

By the early 20th century, the psychological impact of the window display was widely recognized:

"You ask me what there is about a store window that makes a woman irresistibly turn for inspection,"

A.G. Sten continued. "I will tell you. The store window is a woman's great 'reminder.' It recalls to her some need, past or future."

A.G. Sten continued. "I will tell you. The store window is a woman's great 'reminder.' It recalls to her some need, past or future."

As the modern consumer looked through the window pane of glass, she could reflect on the goods displayed. But she also engaged in an act of self-consciousness, reflecting an image of herself onto the display--imagining a longing that could be fulfilled by what was available, imagining a "need" that could be met through a purchase.

|

| The great "reminder," detail, window shoppers |

James McCutcheon's Department Store (pictured above) was located along the aptly named "Ladies Mile" on Fifth Avenue. Its large windows seemed to open up to stage settings, where a world of dreams was laid out. You too can dream about some of McCutcheon's erstwhile products, a few of which are now in the Metropolitan Museum. See one here.

|

| Bird's-eye view of shoppers on 6th Avenue, 1910 |

That feeling, that pit in her stomach, was now also a reminder of an absence that she might never have recognized without seeing these displays. This was, of course, part of the psychological dance prompted by a society based on consumption.

|

| A stage setting of the play "What Life Should Be," aka a window display |

To buy something that somehow could help make life better, easier, happier, prettier, nicer, cleaner, etc. is an act of hope. And to deny that purchase left that emptiness. The longing would remain.

In his 1900 novel, Sister Carrie, Theodore Dreiser perfectly captures this idea. In a visit to a New York department store, Carrie Meeber finds herself:

much affected by the remarkable displays of trinkets, dress

goods, stationery, and jewelry. Each separate counter was a show place

of dazzling interest and attraction. She could not help feeling the

claim of each trinket and valuable upon her personally, and yet she did

not stop. There was nothing there which she could not have used—nothing

which she did not long to own. The dainty slippers and stockings, the

delicately frilled skirts and petticoats, the laces, ribbons,

hair-combs, purses, all touched her with individual desire, and she felt

keenly the fact that

not any of these things were in the range of her purchase. She was a work-seeker, an outcast without employment, one whom the average employee could tell at a glance was poor and in need of a situation. (Sister Carrie, 17.)

As techniques for enticing shoppers into stores through window displays became ever more sophisticated, numerous "experts" on the subject of window displays emerged, giving out advice to merchants. See, for example, "Why Some Windows Fail to Attract," in The Underwear & Hosiery Review, September 1921).

|

| Street Scene, with shadow of photographer, foreground |

In the photograph above, the fact that shoppers were now being keenly observed is suggested in the visibility of the photographer's shadow in the foreground. The woman looks at the photographer, peering out from under her broad brimmed hat, catching the act of observation. (And in fact, in all the images here, the act of observation is present, even if it is not recorded within the image itself).

|

| Cards: One Cent each, East 14th Street |

Stop.

Look!

Behold what awaits you!

Only a thin pane of glass separates you, the window display suggests, from all your heart's desire!

|

| "They're watching you," Bergdorf Goodman, NYC, 1947. |

|

| Lord and Taylor window, NYC, 2007, Christmas, old school. |

~Jenny Thompson

|

| Just This: A Modern Reminder, Tiffany and Co. Window, NYC. |

No comments:

Post a Comment