On December 28, 1972, Diane Keaton appeared on the Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson.

“Would you welcome, Miss Diane Keaton.”

After a discussion of her bangs (prompted by a comment made by Keaton herself) Johnny Carson asked his first question. He was curious about what she was wearing.

Carson: “What are you wearing tonight? It looks like kind of a suit.”

Keaton: “It is a suit. I’m just like you guys. I have a suit on, yeah.”

Carson: “Was it a man’s suit that you had fixed?”

Keaton: “Oh, no. It’s a female suit.”

Carson: “Uh-huh.”

Keaton: “And I am female.”

Carson: “Oh I know that. No, I was…”

Keaton: “Sometimes, you know. . .”

Carson: “There’s no question about that.”

Keaton: “You promise?

Carson: “Yeah.”

Keaton: “You do?”

Carson: “And you’re wearing those clogs again tonight.”

Keaton: “That’s right, yeah, yeah. Well, now that we know what I look like.”

Ed McMahon interjected: “And a lovely blouse.”

It had been several months since the blockbuster film, The Godfather, in which Keaton had a starring role, had been released.

One of Carson’s next questions concerned what presents Keaton had received for Christmas.

Finally, Carson ventured into his guest’s biography. He was surprised to learn that no, she had not grown up in New York City, where she now lived. She had grown up in Southern California and moved to NYC at the age of 19.

“Did you go alone to New York?” Carson asked. Indeed, she had, Keaton responded.

“That’s kind of a big move for a young girl to go to the big city,” Carson said.

YOUNG GIRL, BIG CITY

In 1965, Keaton headed to New York City. Known then as Diane Hall (her real name), Keaton had been accepted into the Neighborhood Playhouse School of Theater (est. 1928), located at 340 E 54th Street. There she studied with famed acting teacher, Sanford Meisner.

When Keaton first arrived in NYC, she stayed at the YWCA. But only for a 3 days. Soon, she moved into the Rehearsal Club at 47 West 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. Housed in a brownstone, the boarding house (women only) operated from 1923 to 1979 and served as inspiration for Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman’s play Stage Door. (Later made into a film by the same name.)

Life at the Rehearsal Club must have been lively. At least it was in its 1937 film depiction of hopeful actresses boarding at the fictional “Footlights Club” at 158 West 58th Street in Manhattan.

After a while Keaton decided to find her own place. At one point she wrote home:

“I’m frantically looking for an apartment. But it’s so hard. The cheap ones go fast, even though they’re located in the worst, most rotten areas. Today I went to the upper west side. No luck. I’m thinking of going to a real estate broker . . . This is more of a hassle than I expected.” (Then Again, 55).

Keaton ended up staying for a year at the Rehearsal Club. In the meantime, her career started to take off.

In 1968, Keaton secured an open-call audition for the musical Hair which had recently opened at the Biltmore Theatre at 261 W. 47th Street (now known as the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre). In the audition, she sang a song and was quickly eliminated. Walking out of the theater, the executive producer “came over to me,” Keaton later recalled, “looked me up and down and said, ‘You stay.’ ” (“Is She Kookie, This Diane Keaton?” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 14, 1972. )

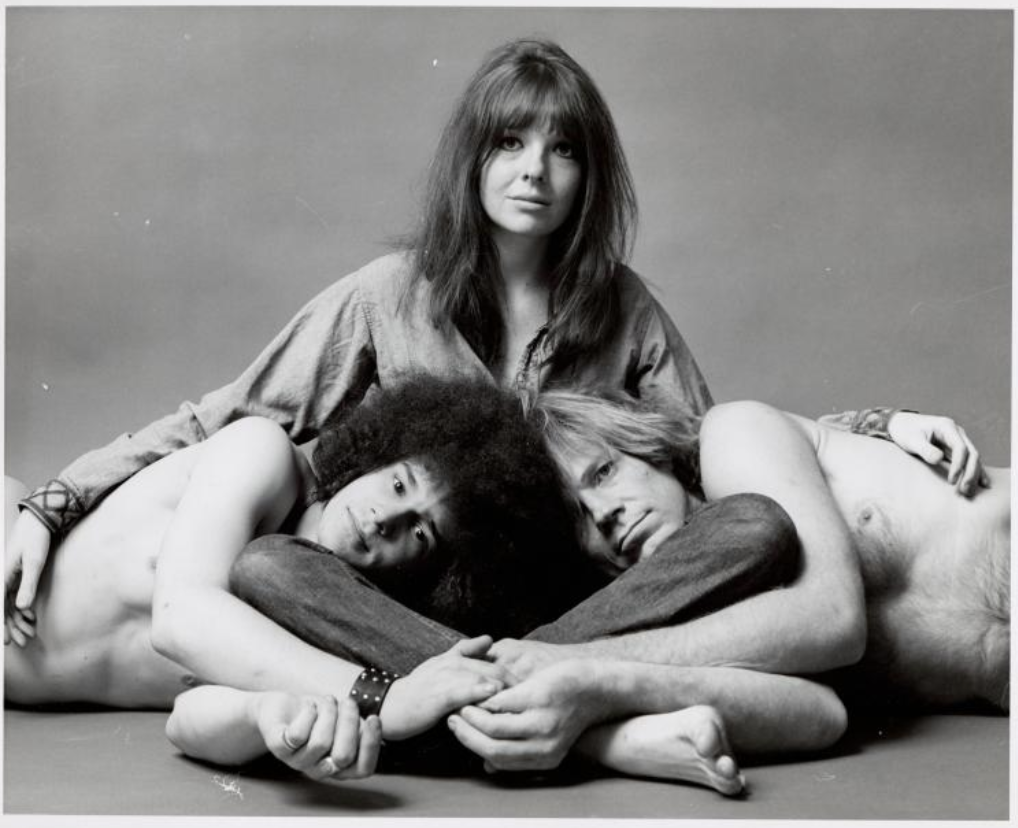

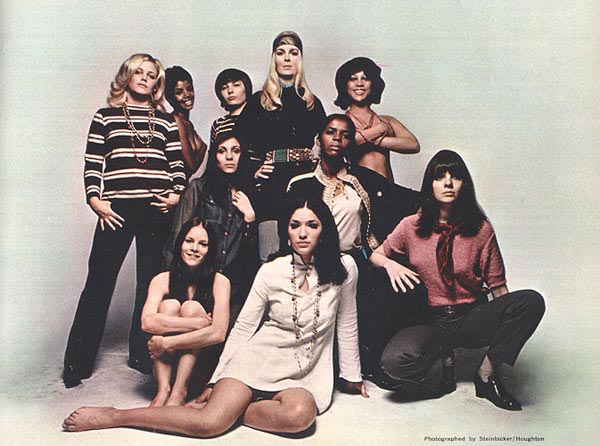

In July 1968, just three months after Hair opened on Broadway, Keaton joined the chorus. She was later promoted to understudy for Lynn Kellogg who played the lead role, Sheila. After Kellogg left the show, Keaton took over the part. (First she was instructed by the producers that she would have to lose weight).

Moving Up(Town)

After her promotion, Keaton finally found an apartment for $75 a month: a studio walk up on West 82rd Street (with a bathtub in the kitchen). The toilet was down the hall.

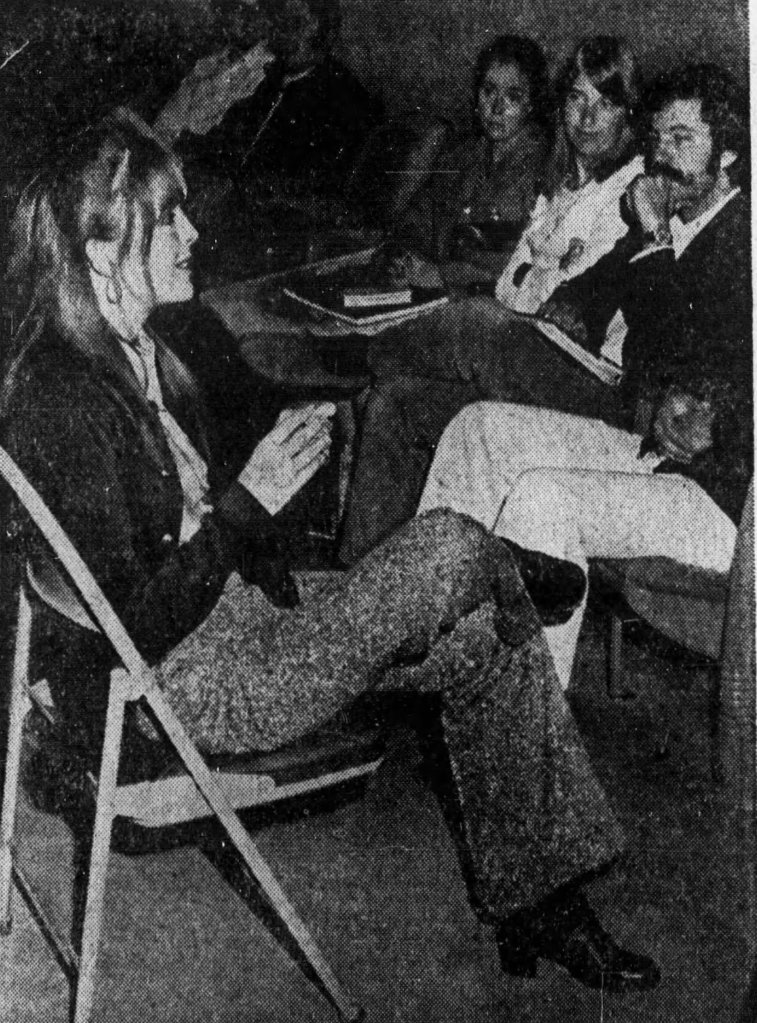

“I know I should find someplace else now that I can afford it,” she told an audience of drama students during a visit back home to Southern California in January 1969. “But I really haven’t had time to look. The place I have now is all right. The only trouble is, it’s right in the middle of the Puerto Rican area and a little scary to walk home to after the show.”

Despite Keaton’s insensitive language, she underscored a NYC in transition in the late 1960s. Just a decade prior to Keaton’s move to the Upper West Side (UWS), a large number of Puerto Rican immigrants had settled there. By 1960, they amounted to roughly 15% of the population of the UWS.

At the time she moved uptown, Keaton was just one of the many young, white singles who trekked to the UWS and took part in the long and ongoing process of gentrification in the neighborhood that is, one can argue, still being enacted.

West Side Story

“This used to be one of the all time freak areas”

72nd St. bar owner to the New York Times, (“Singles Seeking Rapport of ‘Now’ Flock to the Upper West Side,” New York Times, December 28, 1970.)

As Keaton packed up and moved uptown, seeking affordable housing, so did many others. In just a handful of years, the Upper West Side was said to be “experiencing a singles population boom” – as the New York Times reported in 1970, and it was “changing the face of the neighborhood from 72nd to 96th street.”

Indeed, the unnamed bar owner quoted above described how crowds of “straight” people were now flocking to the UWS. But after all, the neighborhood was extremely “cool.” It was “loose.” It was young. And the women of the UWS, as the reported observed, were “more likely to have long hair, wear less make up, [and] are more intellectual.” (“Singles Seeking Rapport of ‘Now’ Flock to the Upper West Side,” New York Times, December 28, 1970.)

“Despite an often raffish appearance and much-discussed crime rate, the West side if becoming, as one resident put it, ‘where the action is.’” Catering to the hip, the young, the less uptight, the neighborhood was transforming with bars, restaurants and businesses now cropping up to appeal to this new crowd. Brownstones were rapidly being renovated into “$250-a-month studio apartments.”

Singles Seeking Rapport of ‘Now’ Flock to the Upper West Side,”

New York Times, December 28, 1970

The Upper West Side had long been under siege by developers, urban planners, gentrifiers, capitalists, and others who sought to stake a claim in an area of the city that had once, long ago, seemed so far away from the “real” Manhattan that it was considered the “country.” (It did, after all, have farms.)

In 1969, just off her stint in Hair, she had fallen into the clutches of W**dy A**en (“discovered” by him, some reporters wrote) and she was cast in the David Merrick production of Allen’s play, Play it Again Sam. After a tour, the play opened on February 12, 1969, at the Broadhurst Theatre at 235 W 44th Street. The play received rave reviews and Keaton was nominated for her first Tony Award nomination.

Soon, Keaton’s had removed south. Her new pad was another apartment whose bathtub was decidedly not in the kitchen. In 1985, she bought an apartment in the San Remo. Her “starter” apartment that went on the market in 2018 for 17.5 million.

Sex and the Single Girl

Keaton would return (cinematically) to her old stamping ground when she starred in the 1977 film, Looking for Mr Goodbar. The film, based on a 1975 book by the same name by Judith Rossner, imagined the larger context to a real-life incident: the murder of Roseann Quinn, a 28 year old single woman who lived on the UWS and was killed by a man that she reportedly met (“picked up”) at an UWS bar called W.M. Tweeds (opened in 1968 and after Quinn’s death renamed All State’s Cafe).

Quinn, who lived across the street from the bar at 253 West 72nd Street, was portrayed in the media as having led a “double life:” stolid and respectable teacher by day and singles bar frequenter by night. She was out on the prowl, sitting in bars, picking up men and ultimately, according to the press coverage (and the film version) she paid the ultimate price for her behavior.

The film version of the story was loyal to the media-shaped version of the story, reiterating the idea that single women were not only unsafe in a scary city full of predators, but they were also “asking for it” by frequenting bars and having one night stands.

“The Single Girl in New York City” headlined an article by Judy Klemesrud that appeared in the New York Times in February 1973. In the wake of Quinn’s death, Klemesrud wrote, many single women were taking precautions: carrying weapons, avoiding subways, or moving to “safer” areas which she called “girl ghettos” – areas where young single women live with roommates or in buildings guarded by doormen. These ghettoes were on the upper east side, however, and the UWS was, according to one woman interviewed in the article, “the most dangerous area of the city for single women.”

But the truth of the story of what had happened to Roseann Quinn was not to be exposed within the frenzy to level an anti-feminist attack on single women and victim blame. In fact, Quinn had not picked up a "stranger;" she knew the man who killed her.

“She wasn’t like they made her out to be.”

Retired NY police detective, speaking about Roseann Quinn.

“She didn’t pick up the guy [who killed her] here,” the detective told a reporter about Quinn in 2007. The "here" he was referring to was the bar where the media had pinpointed as the scene of the "pick up." “He was her boyfriend’s friend and she was showing him around N.Y.C. They went to a couple of places that night before going back to her apartment.”

But the fictional version was so much more useful, wasn’t it? After all, the fictional story was fodder for some good entertainment. In fact, it had been fodder for “one of the best motion pictures ever made!” [sic].

Keaton did win a best actress Academy Award. But not for Looking for Mr Goodbar. She won it for another film she appeared in that same year: Annie Hall.

American Gigolo: Richard Gere with Lauren Hutton.

Three years after Looking for Mr Goodbar was released, critics reacted to American Gigolo's portrayal of the main character's sexuality and sexual identity with far more sympathy (surprise!) than they did to Keaton's character in Looking for Mr Goodbar.

“We leave ‘American Gigolo,’ wrote Roger Ebert in a 1980 review of the film, “with the curious feeling that if women weren’t paying this man to sleep with them, he’d be paying them: He needs the human connection and he has a certain shyness, a loner quality, that makes it easier for him when love seems to be just another deal.”

And he was totally in charge of his clothes:

American Gigolo: Clothes make the man

I almost forgot to mention: What a lovely blouse you’re wearing, Miss Keaton!

~Jenny Thompson

.jpg)